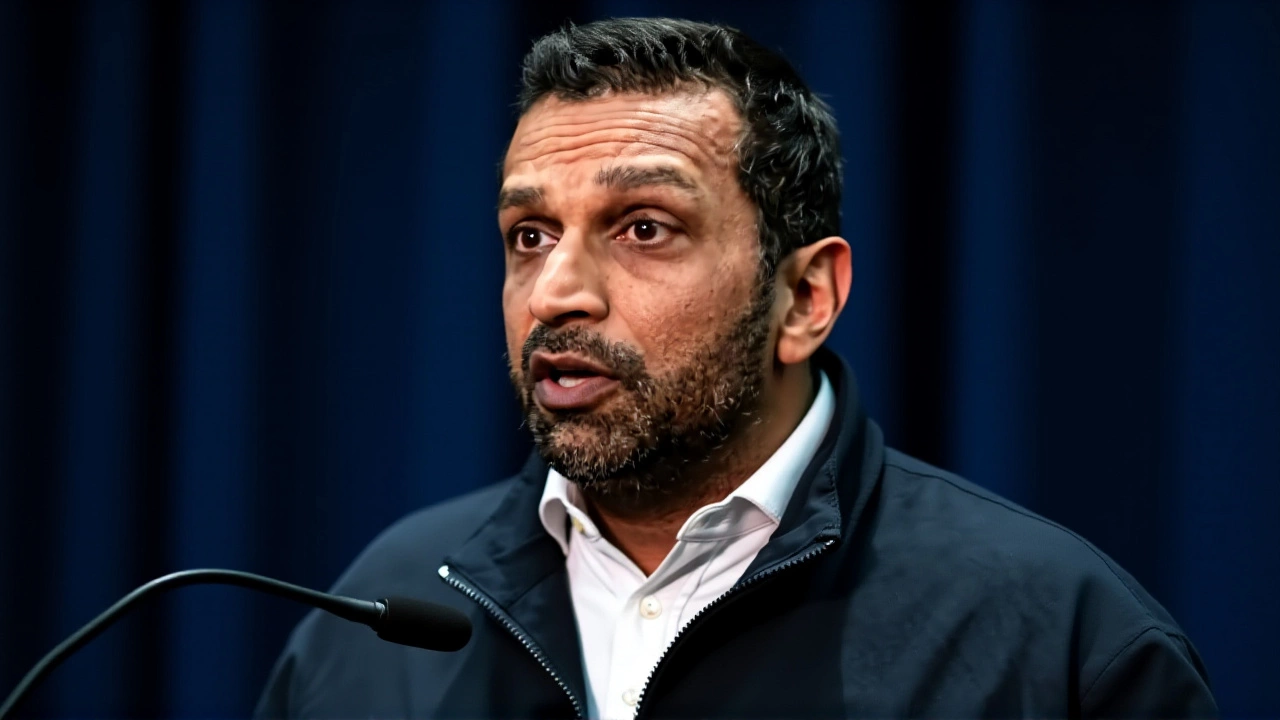

When Kash Patel, director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, handed out plastic replica revolvers to five senior New Zealand officials during a summer 2024 visit to Wellington, he didn’t just make a clumsy gift choice—he broke the law. The gifts, inoperable Maverick PG22 3D-printed pistols, were surrendered within 72 hours and destroyed by New Zealand Police after experts confirmed they qualified as firearms under the country’s strict post-Christchurch regulations. No bullets. No firing mechanism. Just plastic. And still, under New Zealand law, they were illegal.

How a Replica Became a Prohibited Weapon

New Zealand’s gun laws aren’t just tough—they’re uniquely absolute. After the March 15, 2019, massacre at the Al Noor Mosque and Linwood Islamic Centre in Christchurch, where 51 people were killed by a gunman using legally purchased semiautomatics, Parliament moved with astonishing speed. Within 26 days, the Arms (Prohibited Firearms, Magazines, and Parts) Amendment Act 2019 was passed, banning not just military-style weapons, but any device that looks like one. Section 2 of the Arms Act 1983 defines a firearm as “any device designed or adapted to discharge a shot, bullet, or other missile”—no functional requirement. That’s why a 3D-printed plastic revolver, even if it can’t fire, is legally indistinguishable from a real gun.The Maverick PG22 replicas, presented during the August 5, 2024, opening of the FBI’s new legal attaché office, were given to three security officials and two Cabinet ministers: Mark Mitchell, Police Minister, and Judith Collins, then Minister for Defence and the Government Communications Security Bureau. They were decorative, yes—but under New Zealand law, decoration doesn’t matter. What matters is appearance.

The Surrender and the Silence

By August 8, 2024, all five gifts had been handed over to New Zealand Police. Richard Chambers, the Police Commissioner, confirmed the destruction process began that day, following certification by David Goldney, Director-General of the Firearms Safety Authority. The legal trigger? Section 13(1)(a) of the Arms Amendment Act 2019, which mandates disposal of any prohibited firearm or imitation. There was no wiggle room. No “it was just a gift” defense. New Zealand doesn’t issue Category B Endorsements for replica weapons—only 1,842 such licenses existed nationwide as of June 30, 2024, and none were for non-functional items.Here’s the odd part: New Zealand Police refused to release photos of the confiscated revolvers. On August 12, 2024, they denied The Associated Press’ official information request under Section 9(2)(j) of the Official Information Act 1982, claiming disclosure “would be likely to prejudice New Zealand’s relations with the United States of America.” That’s the same law that normally ensures transparency. Yet, the design files for the Maverick PG22 have been on DEFCAD since 2013—publicly downloadable, no restrictions. The U.S. doesn’t ban non-functional replicas under the Undetectable Firearms Act of 1988. So why the secrecy?

Why This Matters Beyond Diplomacy

New Zealand’s approach to firearms isn’t about fear—it’s about culture. With 5.1 million people, the country averages fewer than 10 gun homicides a year. Frontline police officers don’t carry sidearms; only 5.3% do during routine patrols. Guns are treated as privileges, not rights. The Christchurch massacre didn’t just change the law—it changed the national psyche. To gift a replica gun to a minister here isn’t like handing out a novelty keychain. It’s like bringing a replica bomb to a school board meeting and calling it a conversation starter.Patel’s delegation clearly didn’t grasp the context. Or perhaps they did—and assumed the U.S. legal standard applied. That’s the real problem. The U.S. and New Zealand operate under fundamentally different assumptions about guns. One sees them as a constitutional right; the other, as a public safety hazard requiring near-total control. The Maverick PG22 wasn’t dangerous because it could shoot. It was dangerous because it looked like something that could—and in New Zealand, that’s enough to trigger a legal emergency.

What’s Next? A Regulatory Blind Spot

This incident exposes a growing global blind spot: the lack of international alignment on 3D-printed weapons. While New Zealand treats any imitation as a firearm, the U.S. allows them freely as long as they’re non-functional. Germany bans them outright. Canada requires registration. The U.K. treats them as real firearms if they resemble one. No global standard exists. And with 3D printers becoming cheaper and more accessible, the risk of similar incidents will only grow.Will the U.S. State Department issue guidance to its overseas officials? Will New Zealand push for bilateral protocols on gift-giving involving weapon-like objects? So far, silence. But the fact that The Associated Press uncovered this through an encrypted Signal tip from a DOJ source—and confirmed it with five senior New Zealand intelligence officials—suggests this won’t be the last time.

Background: The Christchurch Effect

The 2019 Christchurch attacks didn’t just lead to new laws—they rewrote the rules of public trust. The national buyback program collected 56,246 prohibited firearms by December 2020. The government didn’t just ban weapons; it banned the idea that guns belong in everyday life. That’s why the Maverick PG22 triggered such a swift response. It wasn’t the weapon. It was what it represented: a disregard for a national trauma that still echoes.Patel’s gift may have been meant as a token of partnership. Instead, it became a symbol of cultural ignorance. And in New Zealand, that’s harder to forgive than the violation itself.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why were the 3D-printed revolvers illegal if they couldn’t fire?

Under New Zealand’s Arms Act 1983, a firearm is defined by design or adaptation to discharge a projectile—not by whether it actually works. Even non-functional replicas that look like guns are classified as prohibited weapons. The Maverick PG22 met this definition, triggering mandatory destruction under the 2019 Arms Amendment Act, regardless of functionality.

Who received the gifts, and why did they surrender them?

The gifts went to Police Minister Mark Mitchell, Defence Minister Judith Collins, and three senior security officials. They surrendered them after internal legal reviews confirmed the items violated Section 2 of the Arms Act. No one wanted to risk being charged with illegal possession—especially given New Zealand’s zero-tolerance stance on firearms, even replicas.

Why did New Zealand refuse to release photos of the confiscated revolvers?

New Zealand Police cited Section 9(2)(j) of the Official Information Act, claiming releasing the images could damage relations with the U.S. Critics argue this is an overreach, especially since the Maverick PG22’s design files are publicly available online. The refusal raises questions about transparency versus diplomatic sensitivity.

How does New Zealand’s gun culture differ from the U.S.?

New Zealand treats gun ownership as a privilege, not a right. With fewer than 10 gun homicides annually and only 5.3% of frontline police carrying sidearms, the country prioritizes public safety over individual access. The 2019 Christchurch attacks cemented this stance, leading to sweeping bans on military-style weapons and even their imitations—something unthinkable in the U.S. context.

Could this happen again with other U.S. officials?

Absolutely. Without formal guidance from the U.S. State Department or FBI on international gift protocols involving weapon-like objects, similar incidents are likely. Other countries, like Canada and the U.K., also treat replicas as real firearms under certain conditions. Diplomatic staff need training—not just on protocol, but on cultural and legal realities abroad.

What’s the global significance of this case?

This case highlights a dangerous regulatory gap: while 3D-printed weapons proliferate globally, laws vary wildly. The U.S. permits non-functional replicas; New Zealand bans them. Without international coordination, such diplomatic missteps will continue, and public safety risks will grow as printer technology becomes more accessible worldwide.